The Englishman William Tunnicliff and his wife managed a hotel for the Philadelphia speculator John Nicholson. They hoped to make their establishment on 6th near Pennsylvania Ave SE the center of Capitol Hill life. Tunnicliff's ambitious plans were premised on a steady flow of cash and credit from Nicholson. Like Lewis Deblois, William Prentiss and William Lovering, Tunnicliff wrote frequently to Nicholson begging for money, usually in vain.

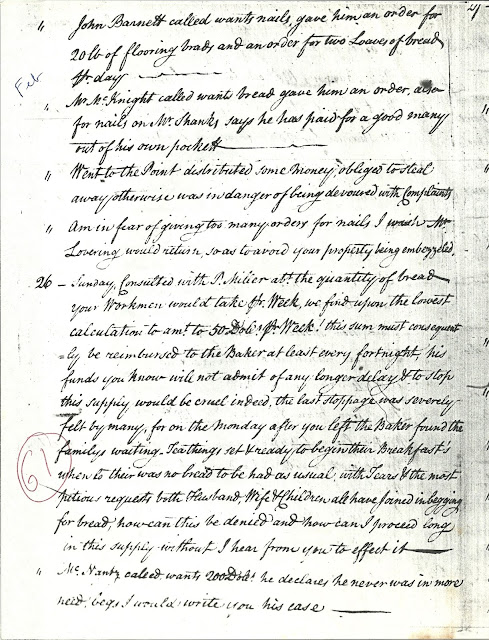

Tunnicliff had the brilliant idea to send Nicholson what he called portions of his diary that noted every instance of his lacking money to carry on his and Nicholson's business. In these diary entries that are in Nicholson's papers, I did not find the word "slave" or "black." That is not surprising. White people in the 1790s rarely wrote about slaves and blacks in general or as a part of the community.

In 1797 upwards of 90 hired slaves worked on the Capitol and White House. Most of them lived in a log hut camp on Capitol Hill. But they were not a part of Tunnicliff's world. Judging from his diary, he owned two slaves. The diary mentions "our boy Sandy" ordered about by his wife, and "my man Tom."

As the diary shows Tunnicliff was overseeing construction which entailed hiring laborers. Since he paid those men directly for their day's work, they were not slaves. There is no mention of their having masters. Only commissioners had the financial resources to hire a large number of slaves. Nicholson did not give Tunnicliff enough money to finance his operations let alone allow him to hire slaves. As the diary shows, providing bread to workers substituted for actually paying them.

The preferred way to always have someone around who would do the menial tasks that always popped up in a rather inconvenient city was to buy a slave who would do the work and who could be sold when, as I assumed happened in Tunnicliff's case, his Washington dreams ended and he moved north.

In time slave hire in the city would become more sophisticated. Some slaves would hired themselves out. But in 1797 whites like Tunnicliff, Deblois and Lovering who tried to establish themselves in the city bought slaves as servants and to do odd jobs.

(You can find larger images of the letters at the end of the post.)

How to buy the book

You can order at History Press as well as Amazon, Barnes and Noble and other on-line retailers. I will send you a signed copy for $23, a little extra to cover shipping. I will send you both Slave Labor in the Capital and Through a Fiery Trial for $40. Send a check to me at PO Box 63, Wellesley Island, NY 13640-0063.

My lectures at Sotterley Plantation in St. Mary's County, Maryland, on September 23, 2015, and the DAR Library on December 5 are now blog posts below listed under book talks. The talk I gave at the Politics and Prose Bookstore on February 28, 2015, along with Heather Butts, author African American Medicine in Washington, was taped by the bookstore. Take a listen.

My lectures at Sotterley Plantation in St. Mary's County, Maryland, on September 23, 2015, and the DAR Library on December 5 are now blog posts below listed under book talks. The talk I gave at the Politics and Prose Bookstore on February 28, 2015, along with Heather Butts, author African American Medicine in Washington, was taped by the bookstore. Take a listen.

Labels

- axe-men (1)

- book talks (2)

- Brent slaves (1)

- bricklayers (4)

- brickmakers (9)

- carpenters (14)

- carters (6)

- Catholic masters (1)

- commissioners and slaves (23)

- contractors (23)

- corrections (5)

- extra wages (7)

- free blacks (2)

- indentured workers (1)

- James Hoban (13)

- L'Enfant (1)

- labor strife (2)

- laborers (24)

- living conditions (25)

- masons (6)

- masters (12)

- new insights (18)

- overseers (15)

- payrolls (5)

- Plowden slaves (2)

- Potomac canal (3)

- private builders (1)

- quarry workers (6)

- Queen slaves (1)

- rivalries (1)

- sawyers (16)

- servants (4)

- slave bricklayers; US Capitol construction (1)

- slave brickmakers (2)

- slave carpenters (9)

- slave laborers (41)

- slave quarry workers (7)

- speculators (3)

- stone carvers (4)

- stone cutters (11)

- stonecutters (4)

- surveyors (3)

- White House (4)

- Williamson (1)

- working conditions (18)

No comments:

Post a Comment